The origins, principles, and enduring legacy of the Bauhaus movement in modern design.

The Bauhaus, founded in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany, is often hailed as the most influential design school of the 20th century. Its revolutionary approach to art, architecture, and design has left an indelible mark on modern aesthetics, emphasizing the harmonious fusion of form and function. This article delves into the origins, principles, and lasting impact of the Bauhaus movement, exploring how it reshaped the world of design.

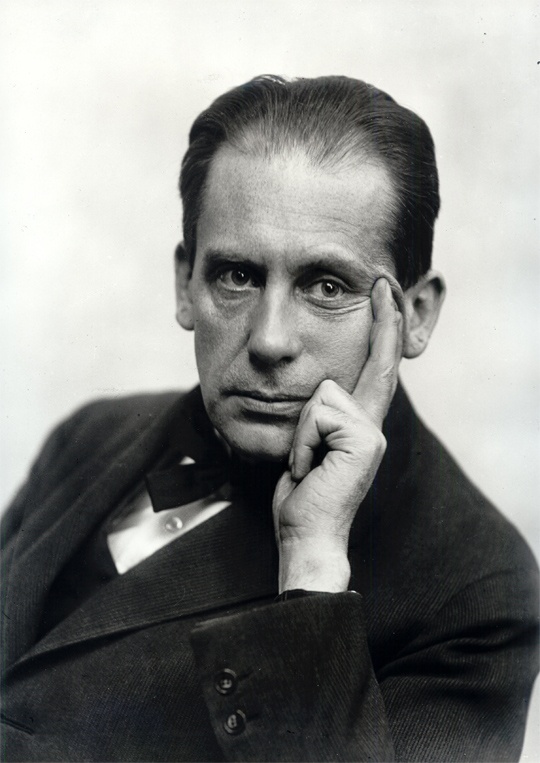

Louis Held, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Walter Gropius established the Bauhaus in the aftermath of World War I, during a time of social and political upheaval in Germany. His vision was to create a school that broke down the barriers between fine arts and crafts, uniting artists, architects, and designers in a collective mission to improve the quality of life through well-designed, functional objects and buildings. Gropius believed that art should meet the needs of society and that the industrial age required a new kind of artist who could combine creativity with technical skill.

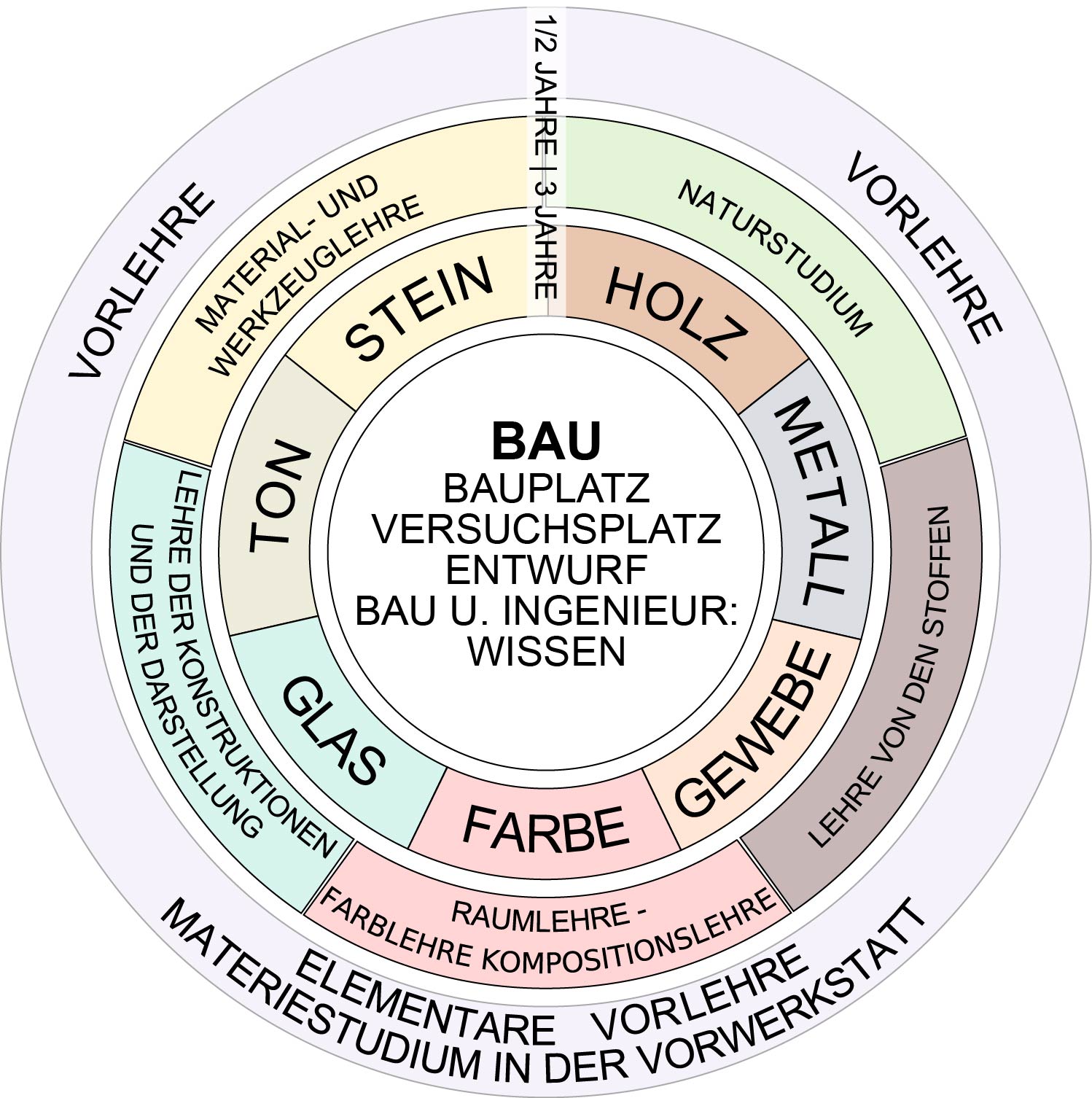

Ralf Herrmann, CC BY-SA 2.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

The name “Bauhaus” itself reflects this vision—literally translating to “building house,” it emphasizes the importance of architecture as the ultimate synthesis of all arts. From the outset, the Bauhaus was revolutionary in its approach, integrating practical workshops with theoretical studies, and encouraging collaboration between students and masters from various disciplines.

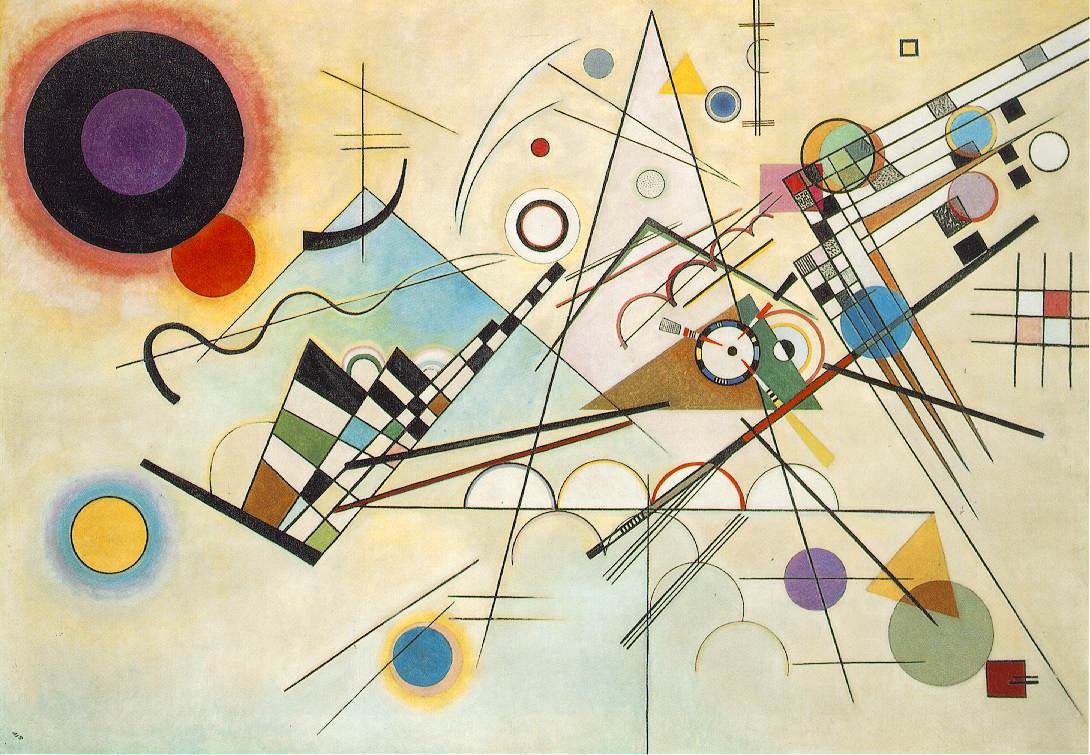

At the heart of the Bauhaus philosophy was the idea of “Gesamtkunstwerk,” or the “total work of art,” where all forms of art and design—architecture, furniture, typography, textiles, and even theater—were brought together in a unified vision. The Bauhaus emphasized functionality, simplicity, and the use of modern materials like steel, glass, and concrete, rejecting unnecessary ornamentation in favor of clean lines and geometric forms.

SuperManu, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

One of the key innovations of the Bauhaus was its emphasis on the role of technology and mass production in design. Gropius and his contemporaries recognized that the industrial revolution had changed the way people lived and worked, and they sought to create designs that could be easily produced and affordable to the masses. This approach led to the creation of iconic designs such as Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair and the tubular steel furniture that became synonymous with modernism.

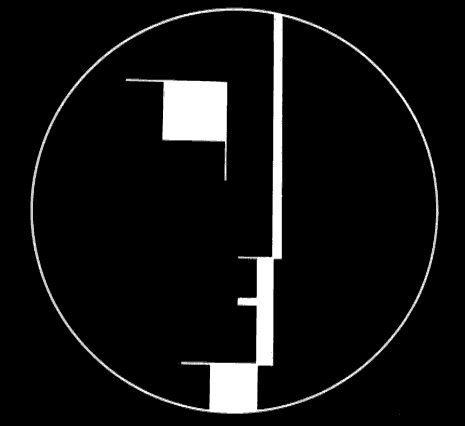

Kai ‘Oswald’ Seidler from Berlin, Germany, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The influence of the Bauhaus extends far beyond its relatively short existence (the school was closed by the Nazi regime in 1933). Its principles have become foundational to modern design education and practice. The Bauhaus laid the groundwork for what we now consider modern design: minimalist, functional, and focused on the needs of the user.

Aufbacksalami, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In architecture, the Bauhaus’s impact is most evident in the development of the International Style, characterized by its emphasis on volume over mass, the use of lightweight, mass-produced materials, and the rejection of unnecessary decoration. Buildings designed by Bauhaus architects, such as the Bauhaus Dessau building by Gropius, are celebrated for their clarity, precision, and functional elegance.

Wassily Kandinsky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Bauhaus was more than just a school; it was a radical experiment in education, art, and design that challenged the conventions of its time. By emphasizing the unity of art and technology, and the need for design to serve society, the Bauhaus revolutionized modern aesthetics and laid the foundation for countless design movements that followed. Its legacy is visible in the clean lines of modern architecture, the functionality of everyday objects, and the minimalist ethos that continues to define contemporary design. The Bauhaus remains a testament to the power of design to shape not just objects and buildings, but the way we live and interact with the world.

Oskar Schlemmer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons